|

Det här materielet bygger på en artikel av urolog Stig Colleen och mikrobiolog Per-Anders Mårdh. Vi har endast gjort sådana utdrag som vi anser belyser sjukdomen rent diagnostiskt. Artikeln är publicerad i boken "Sexually Transmitted Diseases" i kapitel 54 med början på sidan 653. Utgiven på förlag McGraw-Hill, Inc 1990. ISBN 0-07-029677-4

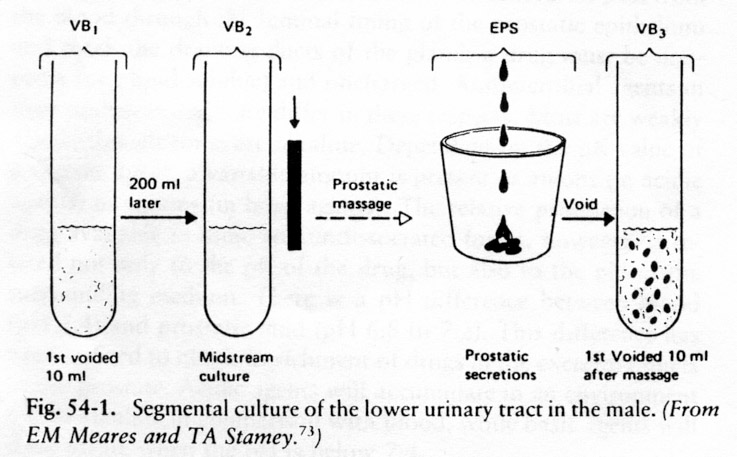

The only way in which the diagnosis of prostatitis can be objective established is by microscopy of expressed prostatic fluid together with quantitative bacteriologic cultures of specimens from urethra and the bladder and from expressed prostatic secretion. To obtain specimen for diagnosis, the patient should have a full bladder and be able to void on request No other precautions are necessary in the circumcised man. In the uncircumcised man, the prepuce is retracted and the meatus is dried with a sterile sponge. The patient is asked to void. The first 10 ml (first voided bladder urine, or VB1) and 10 ml from the midstream portion (VB2), are collected in sterile test tubes for culture and microscopy. Micturition is interrupted before the bladder is empty, and the patient is instructed to adopt a knee-elbow position. The physician then massage the prostate and collects into a sterile petri dish the prostatic fluid (expressed prostatic secretion or EPS) that drips from urethral meatus. If no prostatic secretion appears, pressure applied along the entire urethra half a minute after the massage is ended will generally result in the expected amount of EPS. Finally, the patient is asked to empty his bladder and the first 10 ml of the voided urine (VB3) is collected for analysis (Fig. 54-1).

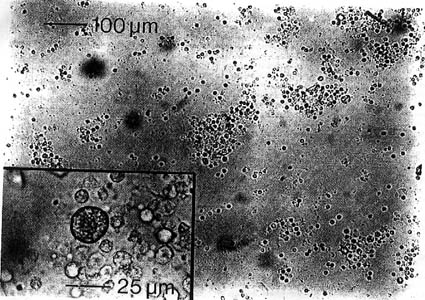

This segmental culture technique is believed to permit determination of the origin of the recovered microorganisms. Thus, if the number of colony-forming units (CFUs) in VB1 significantly exceeds the counts in VB2, EPS, and VB3, the urethra is assumed to be the microbial origin. When the CFUs in EPS and VB3 are at least 10 times more numerous than in VB1 and VB2, the prostate is assumed to be colonized. Concomitant bacteriuria can be eliminated as an obstacle to the diagnosis of bacterial prostatitis by treatment with an appropriate antimicrobial substance, such as nitrofurantoin, which does not significantly penetrate the prostate. the patient is reexamined a few days after completion of the antimcrobial treatment. The VB1, VB2, VB3 and EPS should be sent chilled to the laboratory, where cultures are made with calibrated loop technique: 0.1 ml of the specimen and an equal volume diluted 1:100 in saline are inoculated on blood agar plates and incubated overnight at 37oC. The number of CFUs are determined, and the concentration of bacteria in the original specimens can thereby be established. The reliability of large amounts of pus cells in wet smears of EPS as a sign of prostatic inflammation has been questioned, especially as Jameson demonstrated increased numbers of leukocytes in specimens obtained soon after sexual stimulation and ejaculation (intercourse, masturbation and nocturnal emission). After such stimulation, however the leukocytes count only rarely approaches 20 per high-power (x400) microscopic field. In a carefully controlled study, Andersson and Weller found significantly more leukocytes in EPS from men with symptoms of prostatitis than in EPS from controls without know genital disorders. The number of histiocytes (macrophages and oval fat bodies Fig. 54-2) per cubic millimeter of EPS from prostatitis patients was eight times greater than in the controls. Moreover, there was correlation between the number of histiocytes and the intensity of symptoms reported by the patients. This study and others indicated that a white blood cell (WBC) count of more than 1000 cells per cubic millimeter in EPS (i.e., >10 WBCs per high-power field) is a sign of inflammation of the prostate. A high WBC concentration, however, is found also in patients with urethritis only. The presence of leukocyte aggregates, or rather of cats of pus cells, is mandatory for the diagnosis of prostatitis.

Fig 54-2. Micrograph of an unstained specimen of expressed prostatic fluid orginating from a patient with nonbacterial (idiopatic) prostatitis. Numerous leukocytes, lymphocytes and plasma cells are found, with occasional casts. Inset visualizes a large macrophage with phagocytized foamy material (oval fat body).

The poor correspondence in prostatitis between the cytological findings in semen and in EPS is probably ascribable to the focal involvement of the gland and poor drainage of the affected area at emission. The secretory function of the prostate as a whole is probably impaired in prostatitis, even though the inflammatory process may be focal. This is evidence by diminution of constituents of semen which the healthy prostate secrets in high concentrations (e.g. zinc, magnesium, spermine, cholesterol, citric acid and phosphatase). The pH of prostatic fluid in healthy men is 6.5 to 6.8. In prostatitis the fluid tends to become alkaline and the pH may even approach 8.0 to 8.2. Acidity is restored as the inflammatory reaction subsides. Antibacterial activity of prostatic fluid, which have been reported against gram-negative as well gram-positive bacteria is also affected by the secretory dysfunction in prostatitis. The concentration of lysozyme, which is particularly active against gram-positive bacteria, is likewise reduced in a percentage of patients with prostatitis. The diminution in concentration or activity of constituents with antimicrobiological effect had led to speculations concerning comprised local resistance. If host-parasite relationships are disturbed, urethral commensals might act as pathogens. So far we do not know whether other conditions also may cause secretory dysfunction of the prostate. Consequently, the diagnosis of prostatitis cannot as yet be based on chemical analyses of seminal fluid but must still rely on microscopic examination of EPS.

I nedanstående tabeller visas först i tabell 54-1 några av de vanligaste beståndsdelarna i Prostatasekret. I tabell 54-2 görs en indelning av sjukdomen grundad på innehållet i Prostatasekretet.

Sammanfattning på svenska (ISOPs tolkning) Enligt principen för Stamey localisation. VB1= Den första "urinskvätten". VB2= Den mellersta delen vid urinering. EPS (Expressed Prostate Secret)= Sekret i urinrörets mynning efter prostatamassage. VB3= Urinprov omedelbart efter prostatamassage. Alla dessa prov analyseras (uteslutningsmetoden) m.h.t. till dess innehåll, bakterieodling utföres (vid behov även för Chlamydia trachomatis).

Tillbaka till Bakteriologisk diagnostik

Tillbaka till Behandlingslängd (På sidan Mediciner, behandling m.m.)

Tillbaka till Diagnos (på sidan Prostatasjukdomarna)

|